Have you ever had the flu or the chicken pox? If so, then you've had a close encounter of the viral kind! Whether you dream of one day finding a cure for AIDS or simply hope to avoid this year's flu bug, you're probably familiar with the suffering that can be caused by viral infections (and minimized by vaccines and treatments).

Human viruses come in many types and have a wide range of effects. Some make us sick for a day or two before going away, while others are lifelong. Some are a minor annoyance, while others, such as Ebola, can cause life-threatening complications.

Because of their impact on our health and quality of life, many human viruses (and related animal viruses) have been studied in detail. Let's take a look at some of these viruses.

What does an animal virus look like?

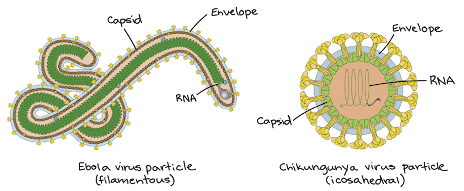

Like other viruses, animal viruses are tiny packages of protein and nucleic acid. They have a protein shell, or capsid, and genetic material made of DNA or RNA that's tucked inside the caspid. They may also feature an envelope, a sphere of membrane made of lipid.

Animal virus capsids come in many shapes. One of the craziest-looking (to me, at least) is the Ebola virus, which has a long, thread-like structure that loops back on itself. A more "standard-looking" virus, chikungunya, is shown below for comparison: chikungunya looks like a sphere, but is actually a 20-sided icosahedron.

Animal virus genomes consist of either RNA or DNA, which may be single-stranded or double-stranded. Animal viruses may use a range of strategies (including some surprising and bizarre ones) to copy and use their genetic material, as we'll see in sections below.

How do animal viruses infect cells?

Animal viruses, like other viruses, depend on host cells to complete their life cycle. In order to reproduce, a virus must infect a host cell and reprogram it to make more virus particles.

The first key step in infection is recognition: an animal virus has special surface molecules that let it bind to receptors on the host cell membrane. Once attached to a host cell, animal viruses may enter in a variety of ways: by endocytosis, where the membrane folds in; by making channels in the host membrane (through which DNA or RNA can be injected); or, for enveloped viruses, by fusing with the membrane and releasing the capsid inside of the cell.

After the virus uses the host cell's resources to make new viral proteins and genetic material, viral particles assemble and prepare to exit the cell. Enveloped animal viruses may bud from the cell membrane as they form, taking a piece of the plasma membrane or internal membranes in the process. In contrast, non-enveloped virus particles, such as rhinoviruses, typically build up in infected cells until the cell bursts and/or dies and the particles are released.

Consequences of an infection

Viruses are associated with a variety of human diseases. The diagram below shows some common examples of viral infections that affect different systems of the human body:

Some viral infections follow the classic pattern of acute disease: symptoms worsen for a short period, but in most cases, the virus is cleared from the body by the immune system and the patient recovers. Examples include the common cold and influenza.

Other viruses, such as the hepatitis C virus, cause long-term chronic infections. Still other viruses, such as human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which in some cases cause the minor childhood disease roseola, may form productive infections (ones where new viral particles are produced) without causing any symptoms at all in the host. In these cases, patients are said to have an asymptomatic infection.

Classifying animal viruses

Animal viruses come in many types, and they enter, commandeer, and exit cells in a variety of different ways. How can we organize this mess of viruses in a way that's consistent and makes sense?

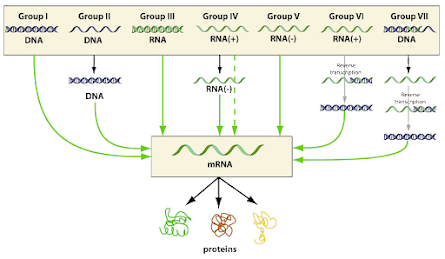

The Baltimore system groups viruses according to their type of genetic material and how it's used to make messenger RNAs (mRNAs), key intermediates in the production of viral proteins and the assembly of new viruses. A virus's Baltimore group depends on:

- The molecule it uses as genetic material (DNA or RNA)

- Whether the genetic material is single- or double-stranded

- The steps the virus uses to make an mRNA

The Baltimore system divides viruses into seven groups. You can see the basic features of each group, including its genetic material and the pathway it uses to make an mRNA, in the diagram below:

No comments:

Post a Comment